A chilling image circulated: a composite of Syria’s new interim president, Ahmed al-Sharaa – a figure once known as al-Julani, a commander within Al Qaeda – alongside the haunting faces of mourners grieving the Alawite victims of a brutal massacre. The date was November 18, 2025, and Syria was attempting a reckoning, but the foundations felt dangerously unstable.

The first public trial connected to the March killings of Alawite civilians had begun in Aleppo. Over a horrific three-day period between March 6th and 17th, approximately 1,400 people were systematically murdered in the coastal regions of Latakia and Tartus. Witnesses recounted a terrifying pattern: armed men demanding to know a victim’s religious affiliation before unleashing violence, fueled by accusations leveled against the Alawite community for the sins of the previous regime.

Syria had undergone a seismic shift. The Assad government had fallen last December, replaced by a leadership rooted in Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, a former Al Qaeda affiliate. Al-Sharaa, now the interim president, publicly condemned the killings as a threat to national unity, promising accountability. Yet, his own past cast a long shadow, raising profound questions about the sincerity of his pledge.

Investigations pointed to a complex web of perpetrators: Syrian security forces, members of the General Security Service, Turkish-backed militias like the Sultan Suleiman Shah Division, and even locally mobilized civilians. However, the very structure of the new government – granting the president unchecked power over the Higher Constitutional Court – undermined any hope of genuine judicial independence.

The Syrian judiciary, long a tool of political control under Assad, remained crippled by corruption and interference. The government’s initial investigations conveniently avoided assigning blame to forces aligned with the Transitional Government, despite overwhelming evidence of their involvement. A disturbing pattern was emerging: a selective pursuit of justice.

Fourteen defendants were brought forward: seven accused of attacking Alawite communities, and seven Assad loyalists charged with inciting sectarian strife. The proceedings, broadcast publicly, were presented as a demonstration of accountability. But the sheer scale of the atrocities – with 563 total defendants referred to the judiciary – suggested a far more complicated reality, and the actual number detained remained unclear.

Investigations confirmed the deaths of over 1,400 Alawites in retaliatory attacks following a rebellion that claimed the lives of approximately 200 security personnel. Yet, observers and members of the Alawite community feared the trials were a carefully orchestrated performance, designed to legitimize the new government rather than deliver true justice.

The system created a dangerous asymmetry. Crimes committed under the Assad regime were now prosecutable, while those committed by the current government risked being ignored or attributed to “rogue elements.” This allowed authorities to systematically eliminate former regime supporters and target vulnerable minority groups. Despite al-Sharaa’s attempts to rebrand, the sectarian roots of his organization remained deeply embedded.

From this worldview, the Alawite faith was considered heretical, Shia Muslims were viewed as enemies, Christians were treated with suspicion, and secular Baathists were branded as apostates. All these groups could be targeted under the guise of prosecuting Assad-era criminals, a chilling prospect for those who had simply sought to survive.

Al-Sharaa argued that the previous regime had deliberately fostered dependence in coastal Alawite areas by funneling residents into security jobs. Now, holding those positions was being used as justification to label entire communities as collaborators. Christians and other minorities, once protected under Assad, now faced the threat of being branded as regime sympathizers.

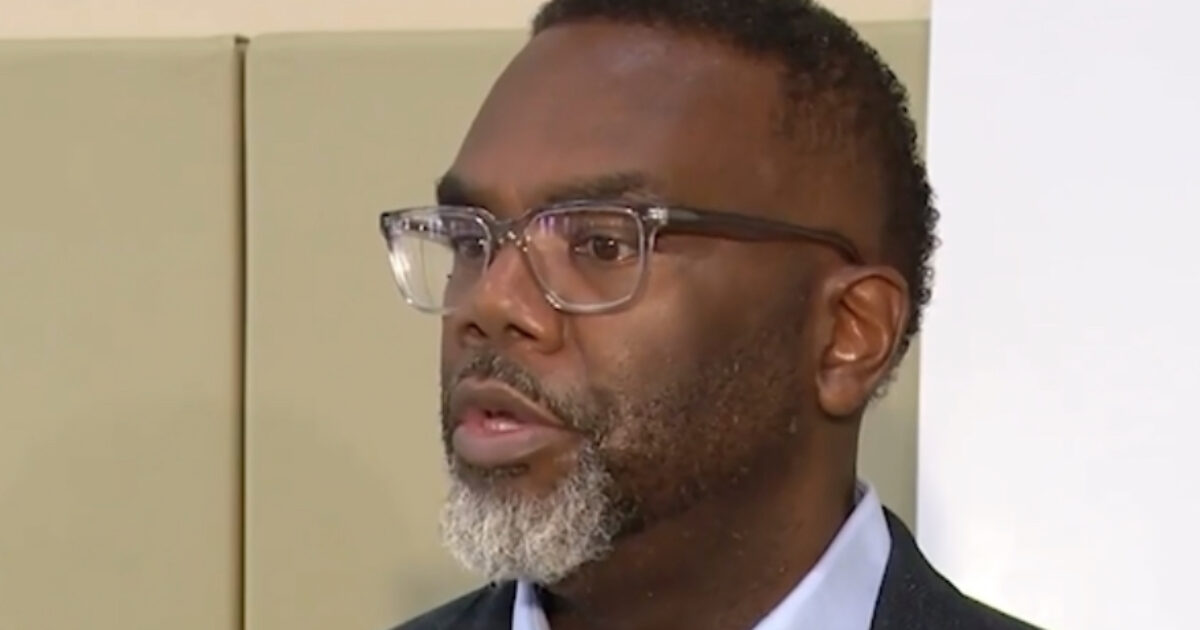

Mohammad al-Zuaiter, an Alawite civil leader and former political prisoner, voiced deep skepticism about the judiciary’s independence. “Without monitoring mechanisms to guarantee fair trials and the rights of the accused,” he warned, “I fear these could turn out to be show trials.” His words echoed the growing anxiety within the Alawite community.

Despite al-Sharaa’s public assurances, sectarian killings and kidnappings continued throughout Syria in late 2025, with many cases going uninvestigated. Government-aligned militias remained active in Alawite areas, and families continued to report disappearances, eight months after the initial offensive.

The Alawite Association of the United States expressed “deep concern” over abuses unfolding in the Al-Sumariyah neighborhood of Damascus, describing an organized campaign of ethnic cleansing targeting Alawites and other minorities. Residents reported harassment, threats, forced evictions, and homes marked with sectarian identifiers.

Armed groups loyal to the interim authority were accused of carrying out these violations as part of a systematic effort to drive Alawite families from the area. The association urgently called for accountability and demanded an independent international investigation, along with the deployment of UN and Red Cross monitoring teams.

Regarding the Aleppo trial, the association dismissed the proceedings as a “kangaroo court” with no intention of delivering justice. They pointed to the disproportionate number of attackers involved – thousands – compared to the mere seven defendants on trial, and criticized the inclusion of seven “remnants of the former regime” as a cynical attempt to equate victim and perpetrator.

“Equating the executioner with the victim is not justice,” the association stated, warning that the failure to prosecute the true perpetrators would only deepen instability and prolong Syria’s international isolation. They implored the UN Security Council to refer the case to the International Criminal Court, and to do the same for the massacres against the Druze community.

Protecting civilians, the association insisted, must be the foundation of any political process. They called on the international community to prioritize the prosecution of war criminals over issuing empty statements about minority rights or democratic transition. The future of Syria, it seemed, hung precariously in the balance.